Fishkeeping is a popular hobby concerned with keeping fish in the home aquarium or garden pond

Types of fishkeeping

The hobby can be broadly divided into three specific disciplines, freshwater, brackish, and marine (also called saltwater) fishkeeping.

Freshwater fishkeeping is by far the most popular branch of the hobby, with even small pet stores often selling a variety of freshwater fish, such as goldfish, guppies, and angelfish. While most freshwater aquaria are set up as community tanks containing a variety of peaceful species, many aquarists keep single-species aquaria with a view to breeding. Livebearing fish such as mollies and guppies are among the species that are most easily raised in captivity, but aquarists also regularly breed numerous other species, including many types of cichlid, catfish, characin, and killifish.

Marine aquaria are generally more difficult to maintain and the livestock is significantly more expensive, and as a result this branch of the hobby tends to attract more experienced fishkeepers. However, marine aquaria can be exceedingly beautiful, due to the attractive colours and shapes of the corals and coral reef fish kept in them. Temperate zone marine fish are not as commonly kept in home aquaria, primarily because they do not do well at room temperature. An aquarium containing these coldwater species usually needs to be either located in a cool room (such as an unheated basement) or else chilled using a refrigeration device known as a 'chiller'.

Brackish water aquaria combine elements of both marine and freshwater fishkeeping, reflecting the fact that these aquaria contain water with a salinity in between that of freshwater and seawater. Fish kept in brackish water aquaria come from habitats with varying salinity, such as mangroves and estuaries and do not do well if permanently kept in freshwater aquaria. Although brackish water aquaria are not overly familiar to newcomers to the hobby, a surprising number of species prefer brackish water conditions, including the mollies, many gobies, some pufferfish, monos, scats, and virtually all the freshwater soles.

Fishkeepers are often known as aquarists, since many of them are not solely interested in keeping fish. Many fishkeepers create freshwater aquaria where the focus is on the aquatic plants rather than on the fish. This is known as the 'Dutch Aquarium' in some circles, in reference to the pioneering work carried out by European aquarists in designing these sorts of aquaria. In recent years, one of the most active advocates of the heavily planted aquarium is the Japanese aquarist Takashi Amano. Marine aquarists often attempt to recreate the coral reef in their aquaria using large quantities of living rock, porous calcareous rocks encrusted with algae, sponges, worms, and other small marine organisms. Larger corals as well as shrimps, crabs, echinoderms, and mollusks are added later on, once the aquarium has matured, as well as a variety of small fish. Such aquaria are sometimes called 'reef tanks'.

Garden ponds are in some ways similar to freshwater aquaria, but are usually much larger and exposed to the ambient climatic conditions. In the tropics, tropical fish can be kept in garden ponds, but in the cooler regions temperate zone species such as goldfish, koi, and orfe are kept instead.

The origins of fishkeeping

Koi have been kept in decorative ponds for centuries in China and Japan.The keeping of fish in confined or artificial environments is a practice with deep roots in history.

Fish have been raised as food in pools and ponds for thousands of years. In Medieval Europe, carp pools were a standard feature of estates and monasteries, providing an alternative to meat on feast days when meat could not be eaten for religious reasons. Similarly, throughout Asia there is a long history of stocking rice paddies with freshwater fish suitable for eating, including various types of catfish and cyprinid. Ancient Sumerians were known to keep wild-caught fish in ponds, before preparing them for meals. Particularly brightly coloured or tame specimens of fish in these pools have sometimes been valued as pets rather than food, and some of these have given rise to completely domesticated varieties, most notably the goldfish and the koi carp, which have their origins in China and Japan respectively. Selective breeding of carp into today's popular koi and goldfish is believed to have begun over 2,000 years ago. Depictions of the sacred fish of Oxyrhynchus kept in captivity in rectangular temple pools have been found in ancient Egyptian art. Many other cultures also have a history of keeping fish for both functional and decorative purposes. The Chinese brought goldfish indoors during the Song dynasty to enjoy them in large ceramic vessels.

Marine fish have been similarly valued for centuries, and many wealthy Romans kept lampreys and other fish in salt water pools. Cicero reports that the advocate Quintus Hortensius wept when a favoured specimen died, while Tertullian reports that Asinius Celer paid 8000 sesterces for a particularly fine mullet.[1] Cicero, rather cynically, referred to these ancient fishkeepers as the Piscinarii, the "fish-pond owners" or "fish breeders", for example when saying that ...the rich (I mean your friends the fish-breeders) did not disguise their jealousy of me.[2][3][4]

Aquarium maintenance

A 335,000 U.S. gallon (1.3 million litre) aquarium at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California displaying a simulated kelp forest ecosystemIdeal aquarium ecology reproduces the balance found in nature in the closed system of an aquarium. In practice it is virtually impossible to maintain a perfect balance. As an example, a balanced predator-prey relationship is nearly impossible to maintain in even the largest of aquaria. Typically an aquarium keeper must take steps to maintain balance in the small ecosystem contained in his aquarium.

Approximate balance is facilitated by large volumes of water. Any event that perturbs the system pushes an aquarium away from equilibrium; the more water that is contained in a tank, the easier such a systemic shock is to absorb, as the effects of that event are diluted. For example, the death of the only fish in a three U.S. gallon tank (11 L) causes dramatic changes in the system, while the death of that same fish in a 100 U.S. gallon (400 L) tank with many other fish in it represents only a minor change in the balance of the tank. For this reason, hobbyists often favor larger tanks when possible, as they are more stable systems requiring less intensive attention to the maintenance of equilibrium.

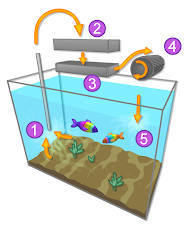

There are a variety of nutrient cycles that are important in the aquarium. Dissolved oxygen enters the system at the surface water-air interface or through the actions of an air pump. Carbon dioxide escapes the system into the air. The phosphate cycle is an important, although often overlooked, nutrient cycle. Sulfur, iron, and micronutrients also cycle through the system, entering as food and exiting as waste. Appropriate handling of the nitrogen cycle, along with supplying an adequately balanced food supply and considered biological loading, is usually enough to keep these other nutrient cycles in approximate equilibrium.

Water conditions

The solute content of water is perhaps the most important aspect of water conditions, as total dissolved solids and other constituents can dramatically impact basic water chemistry, and therefore how organisms are able to interact with their environment. Salt content, or salinity, is the most basic classification of water conditions. An aquarium may have fresh water (salinity below 0.5 PPT), simulating a lake or river environment; brackish water (a salt level of 0.5 to 30 PPT), simulating environments lying between fresh and salt, such as estuaries; and salt water or sea water (a salt level of 30 to 40 PPT), simulating an ocean or sea environment. Rarely, even higher salt concentrations are maintained in specialized tanks for raising brine organisms.

Several other water characteristics result from dissolved contents of the water, and are important to the proper simulation of natural environments. The pH of the water is a measure of the degree to which it is alkaline or acidic. Saltwater is typically alkaline, while the pH of fresh water varies more. Hardness measures overall dissolved mineral content; hard or soft water may be preferred. Hard water is usually alkaline, while soft water is usually neutral to acidic.[5] Dissolved organic content and dissolved gases content are also important factors.

Home aquarists typically use modified tap water supplied through their local water supply network to fill their tanks. Because of the chlorine used to disinfect drinking water supplies for human consumption, straight tap water cannot be used. In the past, it was possible to "condition" the water by simply letting the water stand for a day or two, which allows the chlorine time to dissipate.[5] However, chloramine is now used more often as it is much stabler and will not leave the water as readily. Additives formulated to remove chlorine or chloramine are often all that is needed to make the water ready for aquarium use. Brackish or saltwater aquaria require the addition of a mixture of salts and other minerals, which are commercially available for this purpose.

More sophisticated aquarists may make other modifications to their base water source to modify the water's alkalinity, hardness, or dissolved content of organics and gases, before adding it to their aquaria. This can be accomplished by a range of different additives, such as sodium bicarbonate to raise pH.[5] Some aquarists will even filter or purify their water prior to adding it to their aquarium. There are two processes used for that: deionization or reverse osmosis. In contrast, public aquaria with large water needs often locate themselves near a natural water source (such as a river, lake, or ocean) in order to have easy access to a large volume of water that does not require much further treatment.

The temperature of the water forms the basis of one of the two most basic aquarium classifications: tropical vs. cold water. Most fish and plant species tolerate only a limited range of water temperatures: Tropical or warm water aquaria, with an average temperature of about 25 °C (77 °F), are much more common, and tropical fish are among the most popular aquarium denizens. Cold water aquaria are those with temperatures below what would be considered tropical; a variety of fish are better suited to this cooler environment. More importantly than the temperature range itself is the consistency in temperature; most organisms are not accustomed to sudden changes in temperatures, which could cause shock and lead to disease.[5] Water temperature can be regulated with a combined thermometer and heater unit (or, more rarely, with a cooling unit).

Water movement can also be important in accurately simulating a natural ecosystem. Aquarists may prefer anything from still water up to swift simulated currents in an aquarium, depending on the conditions best suited for the aquarium's inhabitants. Water movement can be controlled through the use of aeration from air pumps, powerheads, and careful design of internal water flow (such as location of filtration system points of inflow and outflow).

Nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle in an aquarium.Of primary concern to the aquarist is management of the biological waste produced by an aquarium's inhabitants. Fish, invertebrates, fungi, and some bacteria excrete nitrogen waste in the form of ammonia (which will convert to ammonium, in acidic water) and must then pass through the nitrogen cycle. Ammonia is also produced through the decomposition of plant and animal matter, including fecal matter and other detritus. Nitrogen waste products become toxic to fish and other aquarium inhabitants at high concentrations.[5]

The process

A well-balanced tank contains organisms that are able to metabolize the waste products of other aquarium residents. The nitrogen waste produced in a tank is metabolized in aquaria by a type of bacteria known as nitrifiers (genus Nitrosomonas). Nitrifying bacteria capture ammonia from the water and metabolize it to produce nitrite. Nitrite is also highly toxic to fish in high concentrations. Another type of bacteria, genus Nitrospira, converts nitrite into nitrate, a less toxic substance to aquarium inhabitants. (Nitrobacter bacteria were previously believed to fill this role, and continue to be found in commercially available products sold as kits to "jump start" the nitrogen cycle in an aquarium. While biologically they could theoretically fill the same niche as Nitrospira, it has recently been found that Nitrobacter are not present in detectable levels in established aquaria, while Nitrospira are plentiful.) This process is known in the aquarium hobby as the nitrogen cycle.

In addition to bacteria, aquatic plants also eliminate nitrogen waste by metabolizing ammonia and nitrate. When plants metabolize nitrogen compounds, they remove nitrogen from the water by using it to build biomass. However, this is only temporary, as the plants release nitrogen back into the water when older leaves die off and decompose.

Maintaining the Nitrogen cycle

Although informally called the nitrogen cycle by hobbyists, it is in fact only a portion of a true cycle: nitrogen must be added to the system (usually through food provided to the tank inhabitants), and nitrates accumulate in the water at the end of the process, or become bound in the biomass of plants. This accumulation of nitrates in home aquaria requires the aquarium keeper to remove water that is high in nitrates, or remove plants which have grown from the nitrates.

Aquaria kept by hobbyists often do not have the requisite populations of bacteria needed to detoxify nitrogen waste from tank inhabitants. This problem is most often addressed through two filtration solutions: Activated carbon filters absorb nitrogen compounds and other toxins from the water, while biological filters provide a medium specially designed for colonization by the desired nitrifying bacteria. Activated carbon and other substances, such as ammonia absorbing resines, will stop working when their pores get full, so these components have to be replaced with fresh stocks constantly.

New aquaria often have problems associated with the nitrogen cycle due to insufficient number of beneficial bacteria, known as the "New Tank Syndrome". Therefore new tanks have to be "matured" before stocking them with fish. There are three basic approaches to this: the fishless cycle the silent cycle and slow growth.

No fish are kept in a tank undergoing a fishless cycle. Instead, small amounts of ammonia are added to the tank to feed the bacteria being cultured. During this process, ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate levels are tested to monitor progress. The silent cycle is basically nothing more than densely stocking the aquarium with fast-growing aquatic plants and relying on them to consume the nitrogen, allowing the necessary bacterial populations time to develop. According to anecdotal reports of aquarists specializing in planted tanks, the plants can consume nitrogenous waste so efficiently that the spikes in ammonia and nitrite levels normally seen in more traditional cycling methods are greatly reduced, if they are detectable at all. More commonly slow growth entails slowly increasing the population of fish over a period of 6 to 8 weeks, giving bacteria colonies time to grow and stabilize with the increase in fish waste.

The largest bacterial populations are found in the filter; efficient filtration is vital. Sometimes, a vigorous cleaning of the filter is enough to seriously disturb the biological balance of an aquarium. Therefore, it is recommended to rinse mechanical filters in an outside bucket of aquarium water to dislodge organic materials that contribute to nitrate problems, while preserving bacteria populations. Another safe practice consists of cleaning only one half of the filter media every time the filter or filters are serviced.

Biological loading

19 Litre Aquarium, seems to be overcrowdedBiological loading is a measure of the burden placed on the aquarium ecosystem by its living inhabitants. High biological loading in an aquarium represents a more complicated tank ecology, which in turn means that equilibrium is easier to perturb. In addition, there are several fundamental constraints on biological loading based on the size of an aquarium. The surface area of water exposed to air limits dissolved oxygen intake by the tank. The capacity of nitrifying bacteria is limited by the physical space they have available to colonize. Physically, only a limited size and number of plants and animals can be fit into an aquarium while still providing room for movement.

Calculating aquarium capacity

An aquarium can only support a certain number of fish. Limiting factors include the availability of oxygen in the water and the rate at which the filter can process waste. Aquarists have developed a number of rules of thumb to allow them to estimate the number of fishes that can be kept in a given aquarium; the examples below are for small freshwater fish, larger freshwater fishes and most marine fishes need much more generous allowances.

3 cm of fish length per 4 litres of water (i.e., a 6 cm-long fish would need about 8 litres of water).[6]

1 cm of fish length per 30 square centimetres of surface area.

1 inch of fish length per gallon of water.

1 inch of fish length per 12 square inches of surface area.

Experienced aquarists warn against applying these rules too strictly because they do not consider other important issues such as growth rate, activity level, social behaviour, and so on. To some degree, establishing the maximum loading capacity of an aquarium depends upon slowly adding fish and monitoring water quality over time, essentially a trial and error approach.

Factors affecting capacity

Though many conventional methods of calculating the capacity of aquarium is based on volume and pure length of fish, there are other variables. One variable is differences between fish. Smaller fish consume more oxygen per gram of body weight than larger fish. Labyrinth fish, having the capability to breathe atmospheric oxygen, are noted for not needing as much surface area (however, some of these fish are territorial, and may not appreciate crowding). Barbs also require more surface area than tetras of comparable size.

Oxygen exchange at the surface is an important constraint, and thus the surface area of the aquarium. Some aquarists go so far as to say that a deeper aquarium with more volume holds no more fish than a shallower aquarium of the same surface area. The capacity can be improved by surface movement and water circulation such as through aeration, which not only improves oxygen exchange, but also the decomposition of waste materials.

The presence of waste materials presents itself as a variable as well. Decomposition is an oxygen-consuming process, therefore the more decaying matter there is, the less oxygen as well. Oxygen dissolves less readily in warmer water; this is a double-edged sword as warmer temperatures make more active fish, which in turn consume even more oxygen. Stress due to temperature changes is especially obvious in coldwater aquaria where the temperature may swing from low temperatures to high temperatures on hotter days.

Fishkeeping industry

Worldwide, the fishkeeping hobby is a multi-million dollar industry, and the United States is considered the largest market in the world, followed by Europe and Japan. In 1994, 56% of U.S. households had pets, and 10.6% owned ornamental freshwater or saltwater fish, with an average of 8.8 fish per household. In 1993, the retail value of the fish hobby in the United States was $910 million.

From 1989 to 1992, almost 79% of all U.S. ornamental fish imports arrived from Southeast Asia and Japan. Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Indonesia were the top five exporting nations. South America was the second largest exporting region, accounting for 14% of the total annual value. Colombia, Brazil, and Peru were the major suppliers. The remaining 7% of ornamental fish imports came from other regions of the world.

Approximately 201 million fish worth $44.7 million were imported into the United States in 1992. These fish comprised 1,539 different species; 730 freshwater species, and 809 saltwater species. The freshwater fish accounted for approximately 96% of the total volume and 80% of the total import value. Of the total of all trade, only 32 species had import values over $10,000. These top species were all of freshwater origin and accounted for 58% of the total imported value of the fish. The top imported species are the guppy, neon tetra, platy, betta, Chinese algae eater, and goldfish.

Several large companies are focused primarily or extensively on supplying the fishkeeping hobby, producing products such as fish food, medicine, and aquarium hardware. Among the largest of these are Eheim, Tetra, Sera, all based in Germany; Hikari, a Japanese company; Fluval, part of the Canadian Rolf C. Hagen group; Interpet, a British company that also owns the Red Sea brand; and the American company Aquarian, owned by Mars, Incorporated but usually trading under the Waltham pet foods brand.

Historically, fish and plants for the first modern aquaria were gathered from the wild and transported (usually by ship) to European and American ports. During the early 20th century many species of small colorful tropical fish were caught and exported from Manaus, Brazil; Bangkok, Thailand; Jakarta, Indonesia; the Netherlands Antilles; Kolkata, India; and other tropical ports. Collection of fish, plants, and invertebrates from the wild for supply to the aquarium trade continues today at locations around the world. In many developing countries, local villagers collect specimens for the aquarium trade as their prime means of income. It remains an important source for many species that have not been successfully bred in captivity, and continues to introduce new species to enthusiastic aquarists.

Fish breeding

A Discus (Symphysodon spp.) guarding its eggs.Fish breeding is a challenge that many aquarists find attractive. While some species reproduce freely in community tanks, most require special conditions, known as spawning triggers before they will breed. The majority of fish lay eggs, known as spawning, and the juvenile fish that emerge are very small and need tiny live foods or their substitutes to survive. A fair number of popular aquarium fish are livebearers, and these fish produce a small number of relatively large offspring, and these will usually take ground flake food straight away (see article on live-bearing aquarium fish).

Animal welfare

At its best, a properly maintained aquarium allows the fish to socialise with their own kind and in many cases breed successfully. This is in marked contrast to the conditions enjoyed by larger animals like cats and dogs, which are often kept alone and neutered in an environment different from that they would experience in the wild. However, in many cases fish are maintained in the wrong conditions and therefore live short lives and never breed. Inexperienced aquarists often attempt to keep too many fish in their tanks, or introduce too many fish into an immature aquarium, with the result that large numbers of fish sicken and die. This has given the hobby a bad reputation among some animal welfare groups, such as PETA, for treating aquarium fish as nothing more than cheap toys that are simply replaced when they die.

Goldfish and bettas in particular have often been kept in cramped bowls or aquaria that are really far too small for their needs.[10] In some cases fish have been installed in all sorts of inappropriate objects such as the AquaBabies Micro Aquaria, Bubble Gear Bubble Bag and Betta in a Vase, all of which contain live fish housed in unfiltered and entirely too small quantities of water.[11][12] The Betta in a Vase is sometimes marketed as a complete ecosystem if a plant is included in the neck of the vase, some sellers claiming the fish will eat the roots of the plant. However, bettas are carnivorous and need to be fed live food or pellet foods as they cannot survive on plant roots. Another problem is that the plant sometimes blocks the betta's passage to the water surface; they are labyrinth fishes, and need to be able to take breaths at the surface of the water or else they will die from suffocation.

These types of products are not really aimed at aquarists but rather at people looking for a novelty gift, and in fact most aquarists abhor them. Similarly, the awarding of goldfish as prizes at funfairs is traditional in many parts of the world, but has been criticised by aquarists and animal welfare charities alike as cruel and irresponsible, and giving away live-animal prizes such as goldfish was made illegal in the UK in 2004.

The use of live prey to feed carnivorous fish such as piranhas also brings criticism.

Fish modification

Modifying fish to make them more attractive as pets is an increasingly divisive issue. Historically, artificially dyeing fish was fairly common, with glassfish in particular often being injected with fluorescent dyes to increase their attractiveness to aquarists. The major British fishkeeping magazine, Practical Fishkeeping, has been effective in its campaign to remove these fish from the market by educating retailers and aquarists to the cruelty and health risks involved.

In 2006, Practical Fishkeeping published an article exposing the techniques for performing cosmetic surgery on aquarium fish, without anaesthesia, as described by Singaporean fishkeeping magazine Fish Love Magazine. The tail is cut off and dye is injected into the body to make the fish more valuable. The piece also included the first documented evidence to demonstrate that parrot cichlids are dyed through injections of coloured dye. Practical Fishkeeping reported that suppliers in Hong Kong were offering a service in which fish could be tattooed with company logos or messages using a dye laser; such fishes have been sold in the UK under the name of Kaleidoscope gourami and Striped parrot cichlid. Some people give their fish body piercings.

Hybrid fish such as flowerhorn cichlids and parrot cichlids are highly controversial. Parrot cichlids in particular have a very unnatural shape that prevents them from swimming properly and makes it difficult for them to engage in their normal feeding and social behaviours. The biggest concern with hybrids is that they may be bred back with true species, making it difficult for hobbyists to identify and breed particular species. This is especially important where hobbyists are conserving species that are rare or extinct in the wild. Even within a single species, extreme mutations have been selected for by some breeders; some of the fancy goldfish varieties in particular have been criticised for having features that prevent the fish from swimming, seeing, or feeding properly.

Genetically modified fish like the glofish are likely to become increasingly available as well, particularly in the United States and Asia. Although glofish are said to be unharmed by their genetic modifications, they remain illegal in many places, including the European Union, though at least some have been smuggled into the EU from Asia, most likely Taiwan, via the Czech Republic.

Conservation

There are two main sources of fish, either from the wild or by captively breeding them. Studies by the United Nations have shown that while more than 90% of the freshwater aquarium fish traded are captive bred, virtually all marine aquarium fish and invertebrates are caught from the wild. The few marine species bred in captivity supplement but rarely replace the trade in wild-caught specimens. Fish and invertebrates that are collected from the wild can provide a valuable source of income for people in regions where other high-value exports are lacking. Marine fish in particular tend to be less resilient during transportation than freshwater fish, and relatively large numbers of them die before they are finally sold to the aquarist. Although the trade in marine fish and corals for aquaria probably represents a minor threat to coral reefs when compared with habitat destruction, fishing for food, and climate change, it is a booming trade and may be a serious problem in specific locations such as the Philippines and Indonesia where most of the collecting is done. Catching fish in the wild can potentially reduce their population sizes, placing them in danger of extinction in the areas where the fish are collected, as has been observed with the dragonet Synchiropus splendidus.

Fish capture

In theory, wild fish should be a good example of a renewable resource that places value on maintaining the integrity and diversity of the natural habitat: more and better fish can be exported from clean, pristine aquatic habitat than one that has been polluted or otherwise degraded. However, this has not been the case with industries such as fur trapping, logging, or fishing where a similar situation existed. Historically, wild resources have tended to be over-exploited rather than managed (see Tragedy of the Commons). Moreover, in places where collecting for aquaria is very intensive, there is good evidence that collecting can result in a decline in fish populations. A particular notorious example is to be found on the Philippines, where overfishing and the widespread use of cyanide to stun the fish has caused a drastic decline in the diversity of the coral reef fish considered most desirable by aquarists.

There are several methods used to catch fish. Fish are caught by net, trap, or cyanide. The most damaging of these techniques is cyanide. It is a poison used to stun reef fish to make them easier to collect. However, it can not only damage fish irreversibly, but even kill them; even if fish or coral are not collected they may remain in contact with cyanide long enough to be killed. It has become in the interest of wholesalers and hobbyists to not purchase fish caught by this method. Because of this, some UK-based wholesalers proudly advertise their lack of cyanide-caught animals. Now, the Philippines have started a movement away from cyanide and towards nets.

The practice of collection in the wild for eventual display in aquaria has several disadvantages. Collecting expeditions can be lengthy and costly, and are not always successful. The shipping process is very hazardous for the fish involved; mortality rates are high. Many others are weakened by stress and become diseased upon arrival. Fish can also be injured during the collection process itself, most notably during the process of using cyanide. This poisoning substance if often used for collecting freshwater species as well, specially in muddy water bodies with lots of vegetation in it, which would make catching small and fast moving fish very difficult.

More recently, the potentially detrimental environmental impact of fish and plant collecting has come to the attention of aquarists worldwide. These include the poisoning of coral reefs and non-target species, the depletion of rare species from their natural habitat, and the degradation of ecosystems from large scale removal of key species. Additionally, the destructive fishing techniques used have become a growing concern to environmentalists and hobbyists alike. Therefore, there has been a concerted movement by many concerned aquarists to reduce the trade's dependence on wild-collected specimens through captive breeding programs and certification programs for wild-caught fish. Among American keepers of marine aquaria surveyed in 1997, two thirds said that they prefer to purchase farm raised coral instead of wild-collected coral, and over 80% think that only sustainably caught or captive bred fish should be allowed for trade.

Captive breeding and aquaculture

Since the Siamese Fighting Fish (Betta splendens) was first successfully bred[citation needed] in France in 1893, captive spawning techniques have been slowly discovered. Captive breeding for the aquarium trade is now concentrated in southern Florida, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Bangkok, with smaller industries in Hawaii and Sri Lanka.[citation needed] Captive breeding programs of marine organisms for the aquarium trade have been urgently in development since the mid-1990s. Breeding programs for freshwater species are comparatively more advanced than for saltwater species. Currently, only a handful of captive-bred marine species are in the trade, including clownfish, damselfish, and dwarf angelfish.

Breeding programs by aquarists have helped to preserve species that have become rare or extinct in the wild, most notably among the Lake Victoria cichlids. Some species of aquarium fish have also become important as laboratory animals, with cichlids and poecilids being especially important for studies on learning, mating, and social behaviour. Aquarists also observe a large number of fishes not otherwise studied, and thereby provide valuable data on the ecology and behaviour of many species.

Captive fish breeding has reduced the final price of many species in the fish trade, allowing a large amount of formerly budget restricted fish be kept by home aquarists. Also, selective breeding has led to several variations among a single species, creating a wider stock of fish in the trade. At this point, however, captive bred marine fish tend to be more expensive than their wild counterparts.

Aquaculture is the cultivation of aquatic organisms in a controlled environment. Supporters of aquaculture programs for supply to the aquarium trade claim that well-planned programs can bring benefits to the environment as well as the society around it. Aquaculture can help in lessening the impacts on wild stocks, either by using raised cultivated organisms directly for sale or by releasing them to replenish wild stock, although such a practice is associated with several environmental risks.

Invasive species

Serious problems can occur when fish originally kept in ponds or aquaria are released into the wild. While tropical species of fish will not live for long in temperate zone climates, fish released into places with similar climatic conditions to those that they originally came from can survive and potentially form viable populations. Species that have established themselves in places that they are not native to are called exotic species. Examples of exotic fishes that have become established outside their normal range are the various species of cichlids in Florida, goldfish in temperate waters, and South American suckermouth catfishes in warm waters around the world. Some of these exotic species can become extremely disruptive preying on, or competing with, the native fish (see invasive species). Many marine fish have also been introduced into non-native waters.

No comments:

Post a Comment